Arab Shorts 2010 curated by Ala' Younis

Arab Shorts 2010 curated by Ala' Younis

Situated on the borders of Arab-ness, this programme highlights the diversity of expression and experimental filmmaking in the Arab world. Through examining the mobility and diversity of thought and history of the image-maker, the programme suggests a wider definition for the Arab and its image. The programme screens footage from a family archive filmed in Kuwait, soars over Jordan, contrasts images of nature in Syria, abstracts a migration situation in Morocco, and reflects on desolated landscapes in Egypt, Lebanon and Finland. It proposes a realignment of the elements of inherited history as well as displacement, in an attempt to contemplate the shape of the Arab terrain, and the role given to this terrain in each of these films.

This programme was curated by Ala' Younis for Arab Shorts, a project of the Goethe-Institut Cairo > arabshorts.net

Ala' Younis will present and discuss the programme.

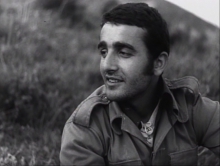

Step by Step, Oussama Mohammad, sy 1979, 22 min

No Title – excerpts from super 8mm films from the family archive, Mufid Younis, jo/kw 1978-1980, 2 min

Tokyo Tonight, Ziad Antar, lb 2003, 3 min

Vacuum, Adel Abidin, iq/fi 2006, 9 min

Linen on Terrace, Fadma Kaddouri, ma/fr 2007, 4 min

Telematch Shelter, Wael Shawky, eg 2008, 5 min

two sides of one piece, Mohssin Harraki, ma/fr 2010, 2 min

Aesthetics of Disappearance, Jananne Al-Ani, iq/jo 2010, 15 min

In his book, A Stone in a Pond, Moroccan artist Mohssin Harraki examines the educational and pedagogical publications that shaped the collective memory of Morocco as a product of post-colonialism. A closer look at old academic curricula in the Arab East reveals that publications studied in Morocco were produced by Dar al-Kashaf in Beirut, which also distributed the same works in Cairo. Until the late 1960s, the Jordanian curriculum was the same as the Syrian curriculum, but packaged in Jordanian book covers. Khalil al-Sakakini wrote books that were studied in schools in Baghdad and Amman. The Arab nation stretches from Mesopotamia to the western edge of North Africa, comprising peoples who are not Arabs and who may not use Arabic as their everyday language. This program is situated on the borders of Arab-ness and its categorization and relies on an examination of displacement and alienation.

Arab nationalism began to gain currency as an elite call for freedom from Ottoman rule and later colonialism. In the 1960s many states adopted the discourse of Arab unity and cooperation spearheaded by Abdel Nasser’s Egypt. Politics exalted, and the economy stimulated, film production. A film pioneer in the region, Egypt had film studios even before India, for example. Even to the present day Egyptian films remain the basic frame of reference for the Arab film industry and culture, and it was not so long ago that Egyptian films were the only ones to enjoy pan-Arab distribution. Independent productions were not known, even in Egypt, beyond very narrow local bounds. The movement of Arab ideas across borders and local vernaculars stopped when it came to cinema in the Arab world. The film program A Lens on Syria curated by Rasha Salti and ArteEast in 2006 was eagerly attended by Jordanian audiences who had heard of Syrian films, but were unfamiliar with them despite the geographical proximity and the reception of Syrian television in Amman. These films had not been, and are not, shown on satellite or terrestrial channels, or in cinemas, and there are no copies of them available in the market. In many cases, they are banned, or have been in the past. It is also difficult to obtain clear copies of Iraqi films produced from the 1950s to 1970s, except for those few copies saved on videotape by the actors.

In Oussama Mohammad’s Step by Step (1979), a large group of people lives a life divided between the field and the school, listening to the words of the father, a man with little education and deep loyalty to the party. The village children learn to obey authority and many join the army. The son may turn against his father: “If my father opposes my party, I’ll be forced to shoot him.” The film portrays how difficult conditions prompt young men to turn to the military, where roles and livelihoods are determined on the basis of rank. Mohammad contrasts captivating images of nature in Syria with the contexts shaped by politics, showing how peaceful communities adopt violence or at least accept its presence on a daily basis.

Wael Shawky brings to life scenes from Arab novels that blend history with fiction, like the works of Abdelrahman Munif or Amin Maalouf, or he re-casts real events like the assassination of Sadat. In his Telematch Shelter (2008), a Bedouin community dreams of settling down to farm. The artist uses elements of typical images of the Arab world to make his commentary: children or non-professionals working as actors, desert locations, and camels and mules instead of cars. A group of children come out of a mud hut and later go back in and shut the door. We don’t know where the children have spent their day or how all of them sleep in such a narrow space. This work is screened on a loop as part of a larger installation titled The Forty-Day Road, a piece about the historical route plied by camel caravans that travel from Sudan to Egypt on a forty-day journey.

The vestiges of economics and politics dominate the forms and discourse of artistic production. In Mohssin Harraki’s video, Two Sides of One Piece (2010), a dirham spins furiously on a white surface. The work is a commentary on the use of money in society and its effects on religion and politics. Coins strengthen the state’s power on the one hand and declare the value of the coin’s owner on the other.

In Ziad Antar’s Tokyo Tonight (2003), we see shepherds and their flocks in a deserted Lebanese countryside on a rainy day. We hear the musical score, and a shepherd faces the camera to confidently declare “Tokyo.” The image returns to the deserted roads, and the shepherds repeat the word “Tokyo” any time they choose. The shepherds don’t seem to be truly obsessed with Tokyo: must all speech be linked to a specific context and time? The artist leaves it to the viewer to navigate between men tending their flocks in the silence of the mountains and a city on the other side of the earth.

Jananne Al-Ani in Aesthetics of Disappearance (2010) soars over the south of Jordan. People become tiny grains of sand moved by the wind as the camera sweeps over archeological sites, the ruins of the Hijaz railroad, military training sites, dried-up water basins, cracked stones, sheep farms, and paved and dirt roads, bringing the modern history of Jordan into view from above. The treatment is similar to Google Earth, which lets you fly above lands you will never set a foot on. Parts of Lawrence of Arabia were shot in the southern Jordanian desert in the 1960s, and both works capture the south from various heights, although the southern landscape looks different in each. This is no doubt partially due to the passage of time, but even more significant is the role given to the terrain in each of these films. Jananne Al-Ani was born in Kirkuk and lived there until the early 1980s when she left for the UK. She has produced a set of video and photographic works based in the Jordanian desert, particularly the section that borders on Iraq. In many of these works, she gathers with her sisters to tell a story that usually revolves around their relationship with a figure that is not physically present in the work. The father, the homeland, Iraq, authority, separation, independence, longing, return—over the years of her work, we see how the relationship with these symbolic figures changes.

Adel Abidin in Vacuum (2006) ventures out into the blanket of snow covering everything in Finland and begins sucking it up with a vacuum cleaner until the snow is gone. In his Cold Interrogation (2002), a Finnish man asks questions of the viewer, like “Do you ride a camel?” These are the kinds of questions that constantly plague Abidin, an Iraqi Muslim who has relocated to Europe.

Moroccan Fadma Kaddouri’s Linge sur terrasse (Linen on Terrace) (2007) portrays would-be migrants who come to al-Nazur in the Rif in northern Morocco with dreams of emigrating to Europe, but are stopped by the terrors of a sea under constant guard and surveillance. Kaddouri is of Amazigh origin and lives today in France, but her work can be considered an Arab work. Every time she visits the Rif with her family, she attempts to re-read not only the history created by migration, but also the history of her father’s land, his home, and everything she is supposed to connect with and learn. Her works also include a set of cassette tape “letters,” a form of correspondence that became popular in the 1980s. Over the course of the correspondence, new messages would be recorded on the same tape, thus erasing the history of the older messages.

We can also read personal and family films as a source to explore the representation of Arab reality. With the beginning of the oil revolution, scores of Arabs went to work in the Arab Gulf states and many returned with video and photo cameras. The program screens footage taken from a family archive filmed in Kuwait and Amman. To preserve the film stock in the 1980s, a VHS video recorder was used to film the footage from a Super 8 screening, and the videotape was then digitized a few years ago. Much visual information is lost in the process of such conversions, just as parts of any family archive are lost as members of the family move apart and relocate or just as the features of Arab-ness change in and outside of the homeland.

The program highlights the diversity of expression and cinematic production in the Arab world, examining the mobility and diversity of thought and history of the image-makers in it. Through the works of the artists, the program suggests a re-definition of the Arab and images of it and proposes a realignment of the elements of inherited history and its uses on the basis of existing cultural forms and artistic expression in the region. This program brings together independent Arab films that are presented at exhibitions and visual arts forums, contemplating the shape of the Arab terrain and attempting to reinterpret it more broadly and deeply, in keeping with the region’s geography and demography. – Ala' Younis