Media Art Redone

Media Art Redone

Assuming that technology evolves very quickly, we might also assume that art made with and about technology changes very fast too. If this were the case, a decade would be an eon when it comes to the evolution of media art. Yet the very fact that it’s still possible to use the term “media art” to describe contemporary practices might have been surprising ten years ago. Many artists and theorists alike predicted the term’s irrelevance and demise long ago, and yet for a panoply of interwoven reasons it persists—albeit with new connotations, instrumentalizations, and proponents.

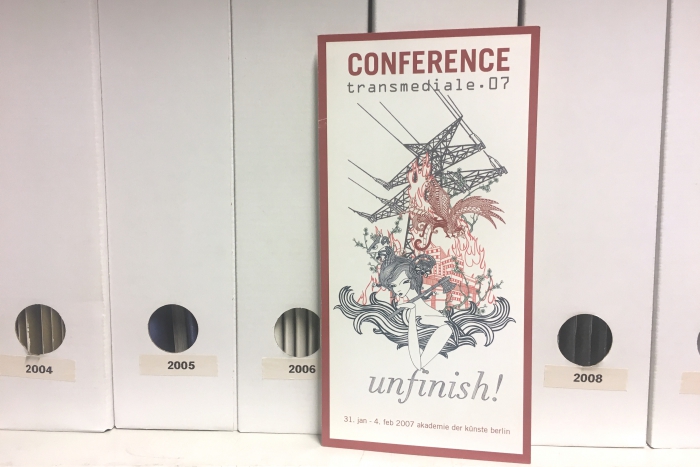

A panel discussion called Media Art Undone that took place at transmediale in 2007 revolved around the categorization of media art as a term and a practice. Unearthing this discussion from the festival archive is to discover a time capsule that, when cracked open, reveals contents much less dated than one might think. From today’s vantage point, the discussion not only remains highly relevant, but in its relevance also suggests a continuity to a discourse that is often reliant on rhetoric of change and rupture.

2007 was an important year for transmediale’s own self-positioning within tricky terminological territories. In only the previous year, the festival subtitle had been officially changed from “international media art festival” to “festival for art and digital culture,” explicitly broadening its scope from art to societal issues, and moreover from the “media art” pigeonhole to a spectrum of creative practices. As became evident in the Media Art Undone panel, a simple change in context or framing fundamentally changes any artwork, and so the new moniker was not only symbolic of a broadening scope but had marked effects on the way the work functioned in context. The panel addressed this reorientation, questioning the power of terminology in transmediale and in the field in general.

The title of the 2007 festival was “unfinish!”—described in the press materials as both the “battle cry” and the “curse” of digital artwork. That is to say: in its ephemerality, media art has historically offered a critical counterpoint to marketable object-commodities, but this impermanence (and dependence on fragile digital mediums) has also hindered its historicization and canonization. Given that by 2007 media art had become a truly “mature medium,” as many speakers on the panel noted, it was time to ask: should media art “graduate” to join the realm of contemporary art, embedding itself into a broad artistic canon? Or should its actors focus on continuing to write a separate, if parallel, institutional history?

Moderator Miguel Leal began by framing the discussion around the term “operative”—how does a term operate in social context, who does it operate upon, and who operatesz` it? “The title Media Art Undone,” he said, “points out to something unfinished or not yet done […] something that needs an un-do: one of those magic operations under the edit menu.” With this he highlighted the irrevocability of terminology once it’s ingrained in practices and surrounding discourse; a term can be steered, borrowed, or appropriated—but undone?

The first panelist was Inke Arns (who is also incidentally co-curating the exhibition program of transmediale 2017). Arns began her presentation by giving examples of the wide-ranging projects that could technically fall under the media art umbrella—citing everything from concrete poetry to social networking experiments. She asked: “why are wall paintings, digital prints on canvas, the infection of the mass media with disinformation, journeys by lorry, or climbing trips all ‘media art’?”

As she and other speakers made clear in their talks, by 2007 media art had clearly “emancipated itself” from the use of the specific media technologies from which it may have originally relied on—and from which it had inherited its name. This had led to a paradoxical situation: a media-specific category was still being widely used to describe a set of practices that were not only unspecific in their use of media, but may in fact be defined as to their disregard for traditional media categories. Media art, after all, had long eschewed the medium-specificity on which the market-driven art world depends. And so, paradoxically, works described as media art could be said to be united precisely in their lack of dependence on any particular media.

“What defines Media Art today is not its range of media,” explained Arns, “but rather its specific form of contemporaneity, its content-related examination of our present.” Implying that it might best be described as an examination of contemporary media culture rather than in any way reducible to any technological, medium-specific substrates, Arns even suggested that media art might better be described just as “Concept Art.”

However, she admitted there are several reasons the term had stuck for so long, which were largely sociological, cultural, and economic: a separate institutional apparatus of festivals and venues; the focus on festivals as an “appropriate format” for presenting media art in the first place; and an unhealthy obsession with “gadgetry” on the part of those who call themselves media artists. Arns ultimately argued that this “ghettoization” of media art might be detrimental to its evolution, and advocated for its entrance into contemporary art at large.

The following speaker, Diedrich Diederichsen, honed in further on the complicated relationship between media art and contemporary art, emphasizing that such categories are outlined by rhetoric, self-contextualization, and social milieu as much as by anything intrinsic to the work itself. He pointed out that all aesthetic artifacts are to some extent dependent on context as opposed to intrinsic properties, and he gave a telling anecdote to explain the often self-imposed divergence between artists in different contexts:

“I want to tell a tale of two artists. They're both—at least they were for a long time—working at the same academy in the same kind of media art or new media department. They were both doing installations with new media, and not so new [media…] But they would never, never ever, be included in the same show, because one was the media artist and the other was a gallery artist. One had an upbringing of art departments and Soho shows and reading October, and the other of Ars Electronica and media labs. So they would do exactly the same kind of work, they would get along quite well, but they would never show together. Why is that so?”

In short, Diederichsen traced those reasons to ones of patronage and lineage. Artists and theorists, like anyone else, often feel a need to inscribe themselves in historical tradition for community, and of course in order to know which grants to apply for. Calling oneself a media artist enmeshes one into a community of those who also use that name; it’s a wearable identity that forges a sense of institutional belonging.

That’s why Olia Lialina, the panel’s third speaker, declared: “If today you introduce yourself as a media artist, it says only at what events you show your works and from what institutions you may be getting grants, but does not say anything about your work, area of expertise, or source of inspiration.” Calling oneself a “net artist or web artist or satellite artist or game artist or home computer musician” would be more appropriate, she said.

Unlike Arns, Lialina did not believe media art as a whole should melt itself into contemporary art. Neither did she seem to believe that would or could happen. She pointed out certain zones of crossover between them to explain how such adoption (perhaps cooption) happens on a more atomized level. For instance, the subset of practices known as net.art had clearly migrated from media to contemporary art by then, a movement made possible by several particular developments. These included both the ubiquity of home computing, leading to the possibility for huge audiences for online work, and the development of more attractive, smaller hardware suitable for showing digital work in gallery settings. “Reducing a computer to a screen, to a frame that can be fixed on the wall with one nail, marries gallery space with advanced digital works.” In these ways net.art (understood as a subset or particular strand of media art) made itself attractive to the contemporary art market, which other subsets had not.

For his part, fourth speaker Timothy Druckrey focused on the illusion of progress that changing terminology perpetuates—updating the label of media art wouldn’t fundamentally change it, but possibly even distract it from changing—and also the outsized dominance of the contemporary art canon in defining what progress means. He expressed resentment at “the October school”—those who have decided to speak for an entire twenty-first century, half of which belongs not to them but to us.” Us in this case referred to the media art world.

Diederichsen, during the discussion, took issue with the idea that there was an “us” and a “them” when it came to media and contemporary art. “You need a large enemy” for that kind of talk, he said, “and I kind of [suspect] this enemy doesn’t really exist, except if we talk about some real, large enemy like capitalism.” He implied that positioning oneself squarely against an abstracted “contemporary art world” might be more akin to splintering the left than to taking a useful political stance.

However, in discussion, theorist Florian Cramer spoke from the audience, pointing out a distinction between the theoretical use of “media art,” which he said “doesn’t make any sense at all,” and the “tactical use,” which has precisely to do with its political capacity. There are, surely, valid reasons to position oneself at an angle to, if not precisely oppositional to, mainstream contemporary art discourse. This is done precisely through naming oneself as part of a separate set of practices with their own institutional and cultural legacy.

Today, one could frame this back-and-forth as a conundrum of branding. Media art as a term is obviously rife with problems as a brand: it antiquates a work before it’s even made by putting a time-stamp on it; it depends on linear concepts of progress that are widely disputed; and the very notion of media specificity is an outdated one. “Contemporary” would really be the best qualifier for such work that sees itself as continually relevant, including but not limited to engaging with media as necessary and reflecting upon use of media in society—but obviously, the qualifier is already taken.

As Lialina alluded to, the market mechanisms of contemporary art, which venues like festivals attempt to provide alternatives to, have the capacity and tendency to subsume and rebrand any practices deemed marketable, leaving others aside. Rather than ask how media artists and theorists choose to position themselves in relation to contemporary art, a better question might be now: is it at all possible to evade the eye of contemporary art in the first place?

Media art, for better or for worse, is still a term in widespread usage, though perhaps more commonly with the prefix “new” or “post-.” These addendums are attempts to both rebrand and to self-historicize: to simultaneously update and to provide continuity. Whether or not this continuity contributes to a continuing “ghettoization” of the field, it also, crucially, allows forgotten or ephemeral practices to be brought to light. Even with the knowledge that all lineages and origin stories are cultural constructions, one needs to trace a lineage to write a history. They are also attempts to unravel the paradox Arns mentioned in 2007 of the media-specificity implied in the term.

If media art was “finally growing up” in 2007, as Arns asserted, it’s certainly old enough now to have had children, who may look nothing like their antecedents. The important thing is that contemporary practitioners are aware of their antecedents, that they have access to information via which to position themselves in relation to what came before. Luckily, one development over recent years is that “the October school” (and its own children) no longer has anything like a monopoly on art discourse. As much as media developments have engendered new platforms for artistic practice, they have fostered new platforms for discourse too.