transmediale Unformatted: A (pre-)History of Thirty Years or More

transmediale Unformatted: A (pre-)History of Thirty Years or More

The “festival format”: a response to an institutional dilemma

Much early media art (including experimental film, expanded cinema, video, sound, and computer art) began in the late 1960s and early 1970s as institutional critique: against the commodification of art (art market, galleries), against mainstream cinema (Hollywood), and against mass media manipulation (especially television). Around the same time, electronic media became more accessible for artistic and DIY practitioners. This resulted in an institutional dilemma: more and more works were being produced but had no place to be shown. This gave rise to the “festival format” as an alternative to permanent institutions for showing works, meeting, exchange, and networking—partly modeled after 1960s experimental film/performance or Fluxus festivals. The era of video and media art festivals reached a peak during the 1980s, with new ones appearing almost every year. Some of them, such as Ars Electronica Linz in 1979 or Videonale Bonn in 1984, began as one-time events that became annual or biennial afterwards.

The coincidence of media theory and media art: “avant la lettre” in 1970s Berlin

Two events in Berlin in 1971 bring us closer to the prehistory of transmediale. At the Technical University, Friedrich Knilli starts to use a U-matic video recorder as technical support for the beginning of what will come to be called media theory. For the first time it is possible to fix the transience of the object onto a storage medium, and German media studies begins with the “ideological critique” of television series recorded on video by Knilli. 1971 is also the founding year of Video-Forum at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.), at the time a unique initiative to make video art more accessible, as there were no permanent collections for the public (and no YouTube, Vimeo, or UbuWeb either). But the real prehistory of transmediale begins six years later, when theory and practice were combined with the founding of the MedienOperative Berlin e.V., a center for independent video work in 1977. Equipped with its own production facilities and working as a collective, the group primarily addressed social and cultural themes, using video as a medium of Gegenöffentlichkeit, or “counter-public.”

The long way to the first Berlin-based “video festival”

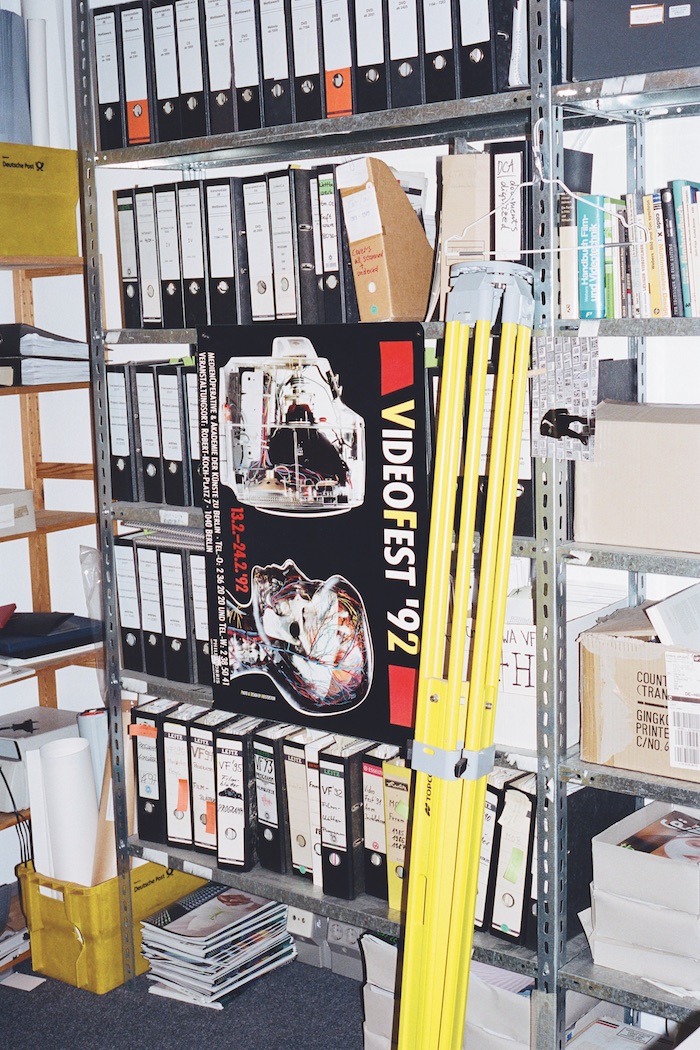

The Berlinale film festival, a US initiative founded in 1950 as a “window to the free world” in the divided city, ran smoothly well into the sixties. Elsewhere, however, by 1968 a rebellion against the “society of the spectacle” and the commodification of cinema was taking place—first at Cannes Film Festival with Jean-Luc Godard, Louis Malle, and François Truffaut, followed shortly after at the Venice Film Festival by Bernardo Bertolucci and Pier Paolo Pasolini. The rebellion reached Berlin in 1970 when the Anti-Vietnam film o.k. by Michael Verhoeven was censored and led to the so called “anti-festival” in 1971, since then established as the International Forum of New Cinema. From 1973, this “film forum” (forum being a popular term at the time, as indicated by the eponymous n.b.k. Video Forum founded the same year) also showcased video contributions. As part of this forum, in 1988 the MedienOperative showed its own program under the name VideoFilmFest, which from 1989 became a regular, stand-alone event under the name VideoFest.

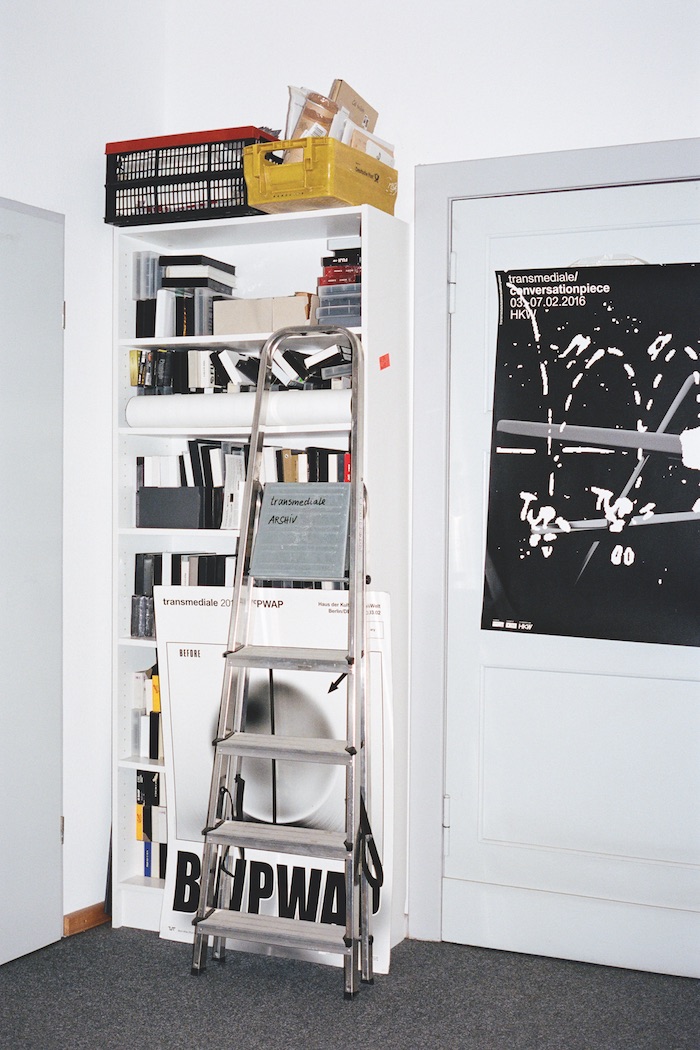

If the 1968 cinema rebellion was late to reach Berlin, so was the idea of a “video festival,” which by the early eighties was well established in other European locations, such as Locarno, The Hague, Montbéliard, Bonn, Marl, Osnabrück, and Rotterdam. But the idea found fertile ground in Berlin on account of this timing; just one year before peaceful revolution in the GDR had brought the Berlin Wall down, and this was right in time to become part of the digital revolution. These two concurrent revolutions—the first won but over, the latter lost but ongoing—are part of transmediale’s legacy. Since then, the festival has become an institution in its own right, but it has also tried to remain “ever elusive” via shifting names and concepts, from VideoFest (1989) to transmedia (1997) to transmediale (1998), and, since 2001, with a yearly changing topic (introduced by Andreas Broeckmann).

The “festival format” unformatted

But why do we still need a festival of any kind when media art has become omnipresent and digital culture seemingly unavoidable? Such a forum for presentation and exchange in real time and real space will neither be replaced by so-called social media nor by post-internet art. One reason for this is the festival’s format—or, more precisely, that it has no format. As a result it is still, to quote the theme of transmediale 2012, “in/compatible” with the commodification of media art and digital culture; the “festival format” is still up-to-date exactly because it resists a final formatting and perpetually reformats itself.